Europe's Muslims May Be Headed Where the Marxists Went Before

December 26, 2004

| |

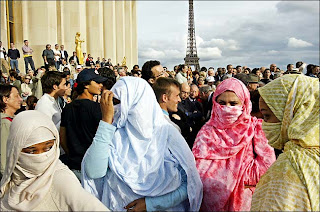

![]() ARIS

ARIS

WHEN Azzedine Belthoub was growing up in the shantytowns outside of Nanterre, France, 40 years ago, the people who came to take the young North African kids to swim in the community pool, to register them for school and give them candy and comic books, were Marxists. The French Communist Party offered a political voice for the working classes, including the growing number of North African immigrants imported to fill labor shortages after the war.

Today, Islam plays that role, especially in France, where men like Mr. Belthoub, wearing long beards and short djellabas, reach out to the poor and disillusioned in the country's working-class neighborhoods. Young Arabs and Africans here have turned to Islam with the same fervor that the idealistic youth of the 1960's turned toward Marxism.

"Now, religion has become our identity," Mr. Belthoub said last week, sitting in a friend's small apartment in a largely Muslim suburb north of Paris.

The question is whether Islam in Europe will follow the same path that Communism did here, shedding its revolutionary extremism, electing mayors and legislators and assimilating itself into normal democratic political life.

As with Marxism in the 1960's, Islam in Europe has its radical fringe and its pragmatic mainstream. The latter is much the broader, intent on expanding Muslims' political power in French society. It has consciously mimicked many of the tactics of the left, including organizing summer camps where urban young people learn the tenets of the movement.

The narrower, but in many ways more potent stream, draws its inspiration from the fundamentalist clerics of Saudi Arabia, and seeks to isolate its adherents from the surrounding society. Though predominantly pacifist, it contains a militant fringe analogous to the violent Marxist groups that operated in Europe decades ago.

That militant fringe makes headlines, though, and colors the whole movement, both in the way young Muslims understand their faith and in the way the larger society sees and deals with Islam, just as the bombers and kidnappers of the Red Brigades and the Baader-Meinhof Gang did to European Communism in the 1960's.

But the eventual evaporation of hard-line Marxism in Europe may offer clues to how the Islamist trend could play out. Disowned by the pragmatic left, Europe's militant Marxist fringe was isolated and repressed, while governments pursued social policies that to some measure addressed the grievances of the poor and dispossessed, which had animated the radicals.

Islam's growth in Europe as the most vibrant ideology of the downtrodden is part of a wave of religiosity that has swept the Arab world in the past 30 years, propelled by frustration over feeble economies, uneven distribution of wealth and the absence of political freedom there.

Like Communism, it represents for many of its born-again adherents a transnational ideology tilting toward an eventual utopian vision, in this case of a vast, if not global, caliphate governed according to Shariah, the legal code based on the Koran.

Many people see the rise of Islam here as a sort of Boabdil's revenge, restoring the faith that withdrew after Boabdil, the emir of Granada, now southern Spain, surrendered the embattled Moors' last foothold in Western Europe 500 years ago.

For them, the religion's return opens another chapter in a centuries-long struggle between Christendom and Islam for the domination of Europe. The Muslim community's high birthrate and the continent's need for more immigration as its native population ages have led to talk about the gradual Islamization of Europe.

But the religion's appeal reaches beyond the communities of Arab and African immigrants born to the faith. There are an estimated 50,000 Muslim converts in France alone today, and the first mosque to be built in Granada since Boabdil's retreat was the work of European converts, not Arab immigrants. Many of these people have taken up the religion as a way to define themselves against traditional European culture, whose values they reject for economic or spiritual reasons.

"Islam has replaced Marxism as the ideology of contestation," says Olivier Roy, a French scholar of European Islam. "When the left collapsed, the Islamists stepped in."

Islam's role isn't entirely accidental. The political left reached out to Muslims during the 1970's, as other groups moved up and out of Europe's working-class neighborhoods. In France, Socialists and Communists alike established associations in the housing projects, attracting many young, politically active Arab men.

But those alliances withered, as frustrated Arab youths turned away from politics. In France, the rupture followed several defining events, including the 1981 bulldozing of an immigrant shelter by the Communist mayor of Ivry-sur-Seine, a Paris suburb. That betrayal was followed by the disillusionment of a 1985 civil rights march that brought little concrete action.

Communist cadres, meanwhile, resisted the rise of young Arabs, known colloquially as "beurs," within their organization. By the end of the decade, when a young Arab man was killed during a demonstration in Paris, the left's credibility in that group was dead.

Islamic organizations soon began channeling the frustrated youth toward religion. Among the first was the Association of Islamic Students in France, which distributed Islamist texts in French. The Tabligh, a fundamentalist missionary movement followed, and in the 1980's, the Union of Islamic Organizations of France became active on university campuses; the union now dominates Islam's growing political role in France.

The map of France's Islamists today largely matches that of the country's Marxists from decades ago. Many predominantly Muslim municipalities are still under Communist-led administrations, but Islamic organizations are now the active ones on the ground. "We see clearly in Lyon, for example, how the structure that was part of the left passed bit by bit in the hands of the Islamists," Mr. Roy said.

The religion's institutional presence has since blossomed. Europe's first generation of Muslim immigrants made do without mosques, halal butchers or easy access to the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that is an obligation of all Muslims; the current generation has all of those things, along with a plethora of educational texts, video and audiocassettes and conferences to expand their knowledge of Islam.

The Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks only increased interest in the religion, and the growing institutions have met surging demand.

"We're rejected everywhere, and so the only place we feel at peace is in our religion," said Issam El-Zryouly, 19, whose family moved to France from Morocco when he was 6. Like many of his peers, Mr. Zryouly has redefined himself as a Muslim after a few aimless years of drug use and petty crime.

But Islam's role as a beacon for the downtrodden may wane, in part because of its very success: the necessary compromises with the surrounding community that are inherent in economic and political participation could dull its edge and sap its momentum, as they did for Marxism.

Beyond the militant minority, the inward-looking fundamentalists are by definition politically insignificant. Once the more mainstream, upwardly mobile Arab or African young people move out of their working-class neighborhoods, "they aren't perceived as Muslim any more, and the vast majority aren't interested in using their religion as a social and political marker," says Gilles Kepel, author of "The War for Muslim Minds."

So, Islam as an ideology of the repressed may hold its allure only as long as the immigrant community's economic and political dislocation lasts.

Comments